Bluefin tuna – an iconic example for recovery

Bluefin tuna is known for its size and price. A new management strategy is to ensure the long-term sustainable management of the stocks in the Atlantic.

Parliamentary elections here, presidential elections there. Politics are omnipresent and certainly don’t draw a line at affecting the world's stock markets. How much should investors be influenced by noise from the left and right when making investment decisions? In this blog we will use Chile, a democratic country, to take a closer look at a stock market currently influenced by political fears. Where uncertainty reigns, the patient investor can usually find opportunities.

Few investors would deny that politics have a great influence on everyday stock market events. The government has the power to reshape framework conditions to companies’ disadvantage (e.g. through higher taxes) but also to their advantage (e.g. through the conclusion of international free trade agreements). Breaking news items and stock mar-ket letters disseminate potential scenarios and thus help with pricing. Thanks to social media, news reports spread ever more quickly and act like an accelerant. Patterns and opinions on the stock market are out of date within minutes or hours, despite the fact that political processes usually take years to have their effect. Experience has shown that political uncertainties have the greatest effect on a single stock exchange when government elections are imminent and there is a threat of sweeping changes. Nerves, and thus volatility, run particularly high when a close election result is forecast. There may be some scientific publications on political stock exchanges, but to our knowledge, science has not discovered any clear and always valid evidence on the connection between elections and stock exchange prices. If you look at the recent past of the world's largest economy, the US experienced a bull market under the internationally-minded President Obama, the nationalist President Trump and also under President Biden, who so far has proved to be a big spender. Stock exchanges held back by politics? Not here. In the short term, i.e. weeks or months before an election, reporting on potential positive or negative scenarios can significantly influence the formation of opinions. For example, the results of early election polls occasionally lead to sharp price movements. Even in the “fish & seafood” universe, we experience political stock markets again and again. As investors with a long-term perspective, it is important to analyse and exploit the opportunities that they provide. Our observations currently point to greater anxiety on the Chilean stock market. At least, we can find no other explanation for the current valua-tions of some salmon farmers listed on the Chilean stock exchange. The Chilean presidential elections will take place in November 2021. At the same time, the Chilean people have decided to rewrite the constitution, which dates back to the times of Pinochet’s military dictatorship. The first election polls on the presidential candidates and the composi-tion of the panel that is drafting the new constitution indicate a shift to the left. Significant outflows from the Chilean stock market since spring 2021 raise the question of the extent to which a left-leaning Chile could truly place the real economy under strain. Viewing Chile as just another socialist South American country falls short of the mark and is a downright affront to the country's basic democratic features.

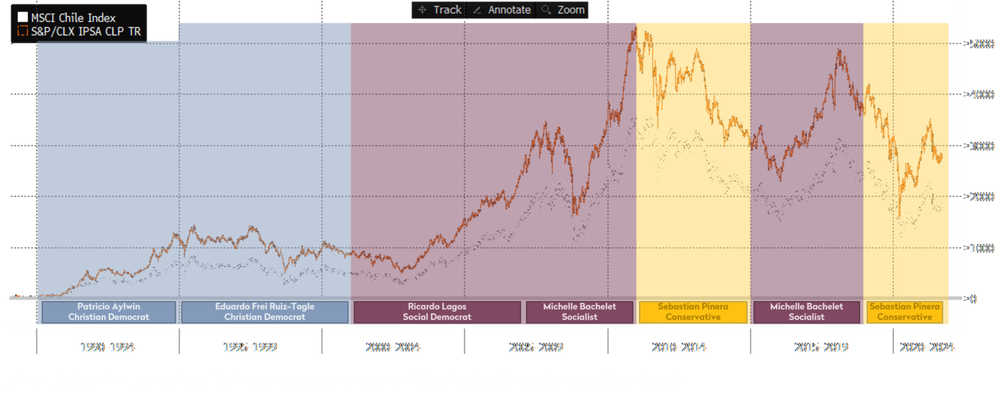

It is rarely a bad idea to take a step back and evaluate the “bigger picture”. Chile's military dictatorship ended in 1988 when long-standing dictator Augusto Pinochet was proved to have committed electoral fraud. Since then, Chile’s democratic system, including free elections, has been restored to full functionality. In nearly 30 years, the South Amer-ican country has been led by just five different presidents. This is the same number of heads of state that France has had in the same timeframe, and represents continuity. Chile even elected a woman to the top post in the form of Michelle Bachelet, who led the country for eight years. We could therefore assume that a female head of government is nothing out of the ordinary these days. Unfortunately, if we look at our French friends, the presidential office still seems to be dominated by men. It is interesting to see that in Chile, parties of different stripes have been in power over the past 30 years. At the beginning of the post-dictatorship period, the country was run by Christian Democrats until the turn of the millennium when there was a shift to the left. Ten years later we saw a political U-turn to favour the conservative billionaire Sebastian Pinera. If we look at the Chilean stock market using the MSCI Chile Index, we see an annual return (in USD) of 9.48% since measurements began in 1987. If we use the local IPSA index, the annual return is slightly higher at 10.83%. In the following graphic we have shown the 30-year period with each president and their political affiliation. What is immediately noticeable on the stock market chart is the phase from 2000-2010 (shaded in purple), when the presidents represented left-wing parties. After a short bear market at the beginning of Ricardo Lagos' presidency, the stock market flourished to a new all-time high in 2010, which to date has never been matched. During this decade, the MSCI Chile Index produced an annual return in USD of 16.46%. We were unable to verify whether the boom shortly before Sebastian Pinera took office was linked to his looming election victory and hopes of a more liberal economic order. The bull market is far from decisive in assessing the “performance” of billion-aire Pineras on the Chilean stock market. Even without this price increase just before he took office, the stock market showed significant negative growth during his term. Less than four years later, Michelle Bachelet took over from Se-bastian Pinera and the stock market experienced a renewed heyday after an initial phase of weakness. As soon as Pinera was re-elected in 2018, the stock market once again fell sharply, even without the bear market caused by COVID-19 at the beginning of 2020. Among changing party leaders, pure index investors have earned an annual negative return of -5.61% from 2010 to today. It therefore seems irrational to paint too gloomy a picture simply be-cause of political shifts.

Simply inferring future events from what has happened in the past is a bad idea. However, facts about the past are useful for creating probable and less probable scenarios, and for putting valuations in a historical context. The politi-cal events of the past few years show one thing in particular: Chile is a functioning democracy. If the citizens are dis-satisfied, whether they are left-wing, right-wing or centrists, there are political movements clearly capable of deter-mining the next president. Conversely, this means that anyone who wants to stay in power in Chile must show a will-ingness to compromise. Otherwise they run the risk of being speedily voted out of office. There is no room for one-sided party politics. Whether you’re in Switzerland, Germany, France or any other democracy, this principle seems to provide social stability. Our most plausible scenario for Chile, that the next presidency will be accompanied by com-promises, would have the same effect. The population at large will not approve of too radical a restructuring. Until a few months ago, when the process of selecting presidential candidates began, the Chilean stock market was in clear recovery mode. The social unrest that first arose in 2019 and caused an international sensation has since been forgot-ten. The bear market of spring 2021 now seems to have bottomed out. If we use the most common valuation multiples applied to the MSCI Chile Index, it seems like a great deal of negativity has been factored in. The price/earnings ratio (P/E ratio) of the index for the last 12 months is currently 15.3x. The average value at the end of the last 20-year period was 21.1x, with only 2008 (the global financial crisis) showing a lower P/E ratio than today (11.0x). The forward P/E ratio as of 31 December, 2021, based on analyst estimates, is just 12.8x. The ratio of enterprise value to EBIT (EV/EBIT) is currently valued at 12.2x, while since 2000 the Chilean stock market has achieved a year-end average of 15.4x EV/EBIT. We can also see a very moderate valuation if we look at the price/book ratio (P/B ratio). The index is current-ly available at 1.4 times the book value of equity, while over the last 20 years it has cost 1.8x on average.

To round things off, we could use some further mathematical tricks to find out the market’s current implicit expecta-tions with regard to valuations in Chile. If we simplify the situation and assume that a change of government would solely lead to higher corporate taxes, the current valuation in relation to the average P/E ratio for the last 20 years would mean that corporate taxes would rise from the current 27% to 47%. Even the most committed socialists cannot be expected to apply such an economically stifling measure, which can therefore be seen as purely utopian.

When considering the "fish & seafood" companies listed in Chile, in addition to political orientation of government we have to take at least two other factors into account. Firstly, this is a small cap area, where a handful of brokers ensure liquidity through block trades with each other. Secondly, analyst estimates lack coverage due to the temporary low level of interest. Both “flaws” can be remedied by having access to the broker network and understanding the com-panies’ business models. The lack of interest from financial investors is still an issue, however; this will require good financial results. And these will follow. As is well known, the COVID-19 pandemic led to drastic shifts in sales channels for food producers. Producers temporarily had to deal with lower sales prices until end consumers were able to find their food products via the new channels again. The balance between supply and demand has since levelled out. In the meantime, the dwindling salmon supply from Chile has become a problem for consumers, meaning that record prices have been paid for Chilean salmon since the beginning of the year. Due to previously concluded delivery con-tracts, the translation of these record prices into companies’ income statements has been delayed by around six months. The lack of analyst reports on the promising price environment and the politically induced outflows from Chile have allowed this market inefficiency to continue. We will use Multi X to show what this means for individual equity valuations. The company produces around 100,000 tons of salmon annually. From 2016-2019 it achieved mar-gins of USD 0.70-1.63 per kilo. Using an average margin of USD 1.20/kg, Multi X would achieve an annual EBIT of USD 120 million. Based on the current enterprise value being paid on the stock exchange, the company’s EV/EBIT ratio is 6.4x. The somewhat cheaper and thus more robust production competition from Norway is valued at around 11.0x EV/EBIT for 2022, which in turn corresponds to a high discount with respect to the food sector, where large companies like Nestlé are valued at 22.8x EV/EBIT. Even more interesting are the prices that large corporations are paying for takeovers in this growth sector. The Brazilian meat company JBS announced that it would pay a takeover price of USD 14.3 per kilo of salmon (annual output) for the Australian company Huon Aquaculture. Applying this purchase price to Multi X, each Multi X share would be worth 650 pesos. On the stock exchange, the share price is listed at a very modest 280 pesos. It would have been a shorter path from Brazil to Chile for a takeover, but those in the industry only sell if they want to or find themselves forced to. Cross-comparisons with previous takeovers, as well as the enormous cost of greenfield investments, once again show that the purchase price is rather modest than overpriced. There is “value” in Chile. Once again, all you need is patience.

Comments