#BlueRevolution - Time to take the plunge

The Fish & Seafood sector provides a historically favorable opportunity. Valuations are at the same level as 2013/2014, while companies have been able to strengthen their positions.

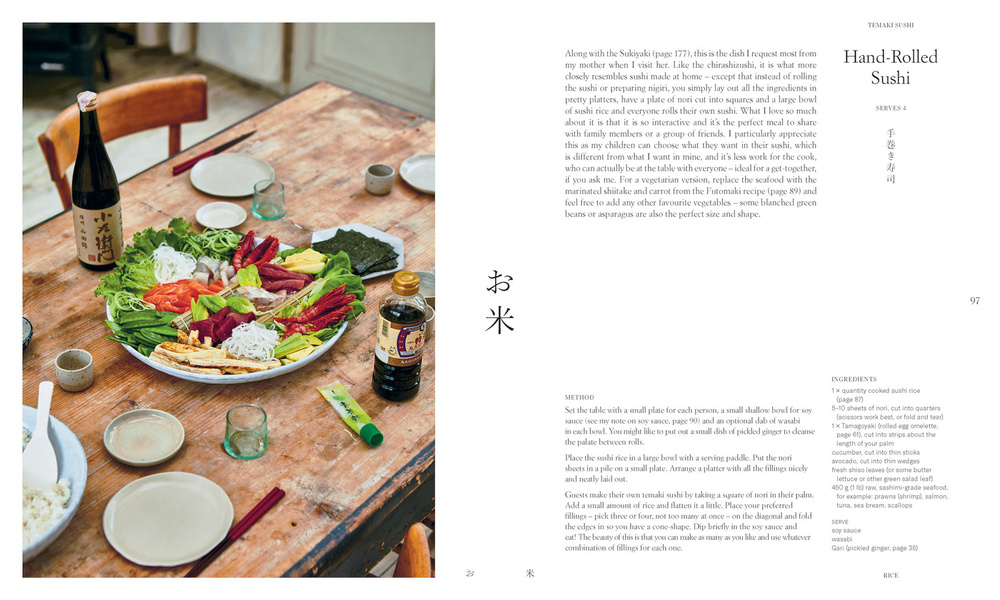

Japanese cuisine and its ingredients are among the best on our planet. While Wagyu and Kobe beef might only be familiar to those deeply knowledgeable in meats, sushi is known to children all around the globe. This exceptionally healthy meal made of raw fish in its various forms has taken the world by storm. The only downside is that Japan forgot to export fish in large quantities along with the traditional recipe. Our journey to the Land of the Rising Sun is a quest to discover whether, thanks to their traditional dish, a new economic sector is belatedly emerging in Japan.

Japan's population is truly a nation of fish eaters, as can be substantiated with numbers: The fish consumption (46kg gross weight) is more than double compared to the global population (21kg). Over 20 years ago, the average person in Japan even consumed over 70 kilograms. The cause for this significant decrease can be attributed to two developments. Firstly, the high consumption was only possible thanks to a strong fishing fleet and little competition. Nearly 8 million tons of wild catch were landed by Japanese ships in the 70s and 80s annually, turning the Land of the Rising Sun into a self-sufficient provider. The subsequent emergence of other nations like China and their claims on fish stocks marked the beginning of the decline for Japan. The vacuum created by the demand for fish proteins was initially filled through imports, thanks to Japan's high purchasing power until the early 2000s.

However, due to the stagnating economic performance from the turn of the millennium, Japan lost its financial strength, leading to a decline in imports. The second noticeable evolution was that the Japanese population, influenced by globalization, began to adopt Western cuisine with a higher meat content. In particular, affordable poultry became increasingly common on Japanese plates. By the year 2020, the self-sufficiency rate in fish for what was once the largest fishing nation had dropped to only 57%.

It may be surprising that while the consumption of sushi has grown significantly worldwide, fish intake has waned in its country of origin. What's more astonishing is that the once-proud Japanese fishing industry failed to profit from the global growth of its traditional dish. Worse still, they ceded the field to other coastal nations like Norway with their Atlantic salmon, even though, according to traditional Japanese recipes, this fish was never used in sushi dishes. What did the export nation of Norway do better? They invested early in aquaculture, recognizing that wild catch was stagnating and that marine fish could be successfully farmed. In addition to self-sufficiency, it could also be argued that Japan, in favor of quality, consciously chose not to export perishable fish, preferring to offer the world their cuisine with freshly caught fish in their own country.

Japan, being an island nation somewhat isolated northeast of other Asian countries, has seen its fair share of changes, especially with advancements in technology and logistics for freezing. During our stay in Japan, we found considerable efforts being made to catch up on this missed opportunity. Aquaculture for traditional sushi fish is just beginning, and it's quite possible that Japan might replicate the successful growth story of the Atlantic salmon. With political backing to increase self-sufficiency, the environment for investments is extremely attractive.

Is there a secret formula for the industrialization of fish farming? Well, not all fish are the same, but most species and aquacultures share commonalities. Thus, one can learn from success stories like those in Scandinavia. The Norwegian pioneers invested decades in the genetics of salmon, breeding the best specimens together. These fish became more robust and converted feed into growth more efficiently. This helped save costs and provide an affordable protein source in Europe. With the growing industry along the coast of Norway, supply companies emerged, developing solutions and services that made farmers more efficient. Non-core business activities were outsourced.

This accumulated know-how and regular exchanges in cooperation or at conferences eventually led to the formation of clusters. These interactions, combined with profitability due to lower production costs, exponentially lead to innovations that enable technological progress and eventually solve major problems. To prevent market oversupply, controlled growth through licenses for defined volumes is needed, which Norway implemented in the past decade. Finally, the task is to create global demand for fish proteins. This can be achieved through promoting quality characteristics or suggesting recipes. However, for a commodity like fish, a national organization is required, capable of conducting targeted marketing campaigns with broader financing. The brand "Seafood from Norway" is backed by a strong industry organization created precisely for such joint advertising purposes.

In genetics, Japan focuses on developing well-known sushi fishes like Yellowtail Kingfish or Amberjack, accustomed to the southern domestic water temperatures. Work is also being done on tuna. The selection programs have been running for about 15 years, involving academic institutions like universities. Progress is evident, as there are successful land-based factories producing hundreds of thousands of fry for coastal facilities. The formation of a supplier industry and clusters is still somewhat modest. However, innovations like new cage technology are supported with government subsidies and loans. A significant advantage for Japan is the presence of financially strong seafood conglomerates capable of cross-subsidizing losses with funds from other areas. This long-term orientation is typically Japanese.

There are skilled people at work in Japan who enjoy innovating and experimenting, while always being cost-conscious. Where Japan needs to catch up is in global marketing. The country's counterparts in land-based industries with their Wagyu and Kobe beef have been very successful in achieving premium prices. Thanks to the fame of sushi, it could be an easier task for aquacultures and their fish. Like Swiss cheese, Scottish whiskey, or Spanish cured ham, we might start hearing about Japanese fish in the European or American markets within the next ten years.

Comments